The trial of Kings Cross

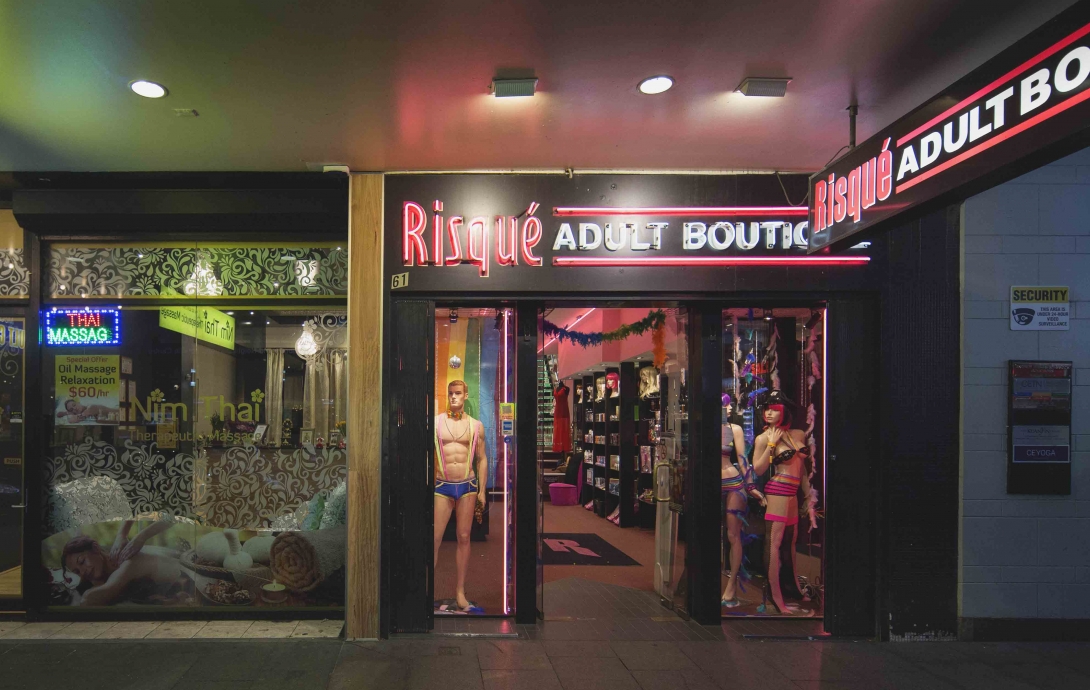

Kings Cross has become a flash point for Australian’s love affair with danger. Once a buzzing red light district, this tiny locality is now a shadow of its former self. Kings Cross is on the operating table; will it live or die?

With boarded up shops and ‘For Lease’ signs, The Cross is struggling to attract the hordes of revellers it once entertained ‘til the wee hours.

The Cross has taken a hit from all sides. Locals say it’s been attacked by our Baptist Christian NSW Police commissioner Andrew Scipione; hemmed in by laws introduced by ex-premier Barry O’Farrell; and neglected by the planning departments of City of Sydney and State Government. Developers like Greenland are now standing by, to use the land for residential developments.

The controversial lock out laws which have demolished foot traffic by as much as 80%, are the same laws credited with decreasing street violence. Last year some claimed The Cross would become a mini Manhattan, an extension of cosmopolitan Potts Point, with upscale shopping and restaurants side-by-side.

Ex-nightclub owner John Ibrahim says The Cross is dead.

“There is no more Kings Cross. The whole vibe, they’ve choked it all out,” Ibrahim says. “I agree something had to be done, but Kings Cross was a knee-jerk reaction by State Government to a few violent incidents,” he says.

Urbanist and local resident Frank Elgar agrees. He has witnessed the gradual demise since the late sixties.

“From the El Alamein fountain down to Coca-Cola sign it is hideous. It’s just seedy. I lived in The Cross in the sixties, ’68 and ’69 and I knew it when it was the most European of all the suburbs in Australia. I knew it before it was destroyed by the R&R,” he says.

Elgar describes how The Cross was turned into a “mini Bangkok” during Vietnam War featuring every type of excess in drugs and prostitution. At that time thousands of American serviceman were allowed to come to Sydney for ‘Shore Leave’ thanks to the Cross’s proximity to the international naval base.

“That was like the sacking of the city,” Elgar says.

Cabaret singer and show biz icon Maria Venuti also recalls The Cross when it was full of colour and adventure.

“It used to be good; so social and so Bohemian. Now there’s a sadness and a feeling that it’s all become too mediocre and plain. Everyone used to say, “Let’s go up the Cross”. It was exciting. You couldn’t walk ten yards without seeing someone you knew or without looking in a beautiful jewellery store or having a drink at great cafes like Sweethearts,” Venuti says.

Indeed for a place once immortalised by songs like Breakfast at Sweethearts by Cold Chisel and by poets like Kenneth Slessor, it’s obvious that positive odes to Kings Cross are now hard to find.

“The Cross has always been a busy and vibrant neighbourhood,” says Justin Maloney, ex-proprietor of longtime resident Jimmy Liks, which closed its doors on Victoria Street in January.

“Kings Cross today is like a ghost town. It is having an identity crisis. ” Maloney says.

For those who have lost their business, the clean-up of the streets has been a bitter pill to swallow. Large and small businesses are going bust. “I was the 33rd business to go under when I closed the doors,” says Justin Maloney.

“There was a time when something could have been done through extra policing. But the state government and the City of Sydney just let it get darker and darker. They stood by and watched it die.”

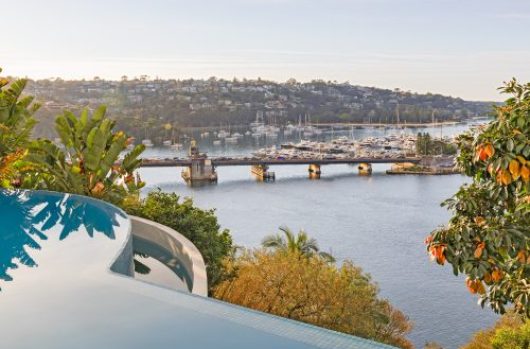

According to Ibrahim, Sydney desperately needs a vibrant night time economy, not another residential suburb.

“The truth about The Cross has been brushed under the carpet. These ‘Wise Men’ that made these decisions for us – because they decided we are all to be treated like children – were completely wrong. Might I also point out that 35% of these men who made these decisions in the public’s good interest, were stood down or resigned from government straight after the laws were introduced. These so-called wise men were crooks themselves!”

Frank Elgar says more action was needed when The Cross was heading to extremely low standards.

“There was an intensification in Kings Cross, because there was an abundance of long licences and all sort of things were permitted and allowed. The problems of that intensity are due to the pattern of selling patrons too much alcohol and packing them into places where they are not served food. The whole culture of alcohol in Australia is shocking.

“This is a very, very bad situation of social planning. A lot of young people were allowed to come to The Cross and many of the hotel operators and attendant people were double handed. All the venues were heavily guarded by thugs whose only qualifications were their release papers from the Long Bay jail.

“Now that there is a lock out, all these people have fled and are destroying King Street, Newtown,” Elgar says.

Ibrahim agrees lock out laws are just a “moron relocation program.” He also identifies Newtown as the next victim.

“There is still violence. There are still violent incidents happening every weekend elsewhere. They are just not being reported. We have not addressed the real problem. People are still buying alcohol. Kids are still buying alcohol, they are just buying it from Woolworths instead of from a publican. This is a policing issue. Not an alcohol issue,” Ibrahim says.

Those who remember the pavements five deep with drunks and the chaos of ambulances up and down the strip might argue the lock out laws have provided a welcome reprieve for hospital workers in emergency. The government states that statistics on restaurant dining are up and benefiting from the lock out laws.

Restauranteur Sam Christie, who works in bordering Potts Point, says while lock out laws have effectively cleaned up the streets, they have also changed the feeling in the area.

“Kings Cross is pretty sad today compared to what it was. I have been going out and working in The Cross since 1985 and for my generation The Cross was not only a place to go out and party the night away, but to eat and socialise especially after work. The demise of Kellett Street was the beginning of the end.

“There was always aggression and overdoses and lots of that stuff going on, but you see that in any big Anglo-Saxon city. As an aside I was also king hit from behind on the corner of Darlinghurst Road in 1993. I think this area is the most high density suburb in all of Australia. Now there are so many less people out at night than 2-3 years ago. I can’t help but think that the lock out laws have caused this,” he says.

Without the epicentre of The Cross and a plethora of larger venues to pull in the crowds, there is a question over whether smaller character venues will be able to attract the numbers they need to stay open. Who will welcome those finishing their shifts in restaurants and bars after work?

Right now in The Cross there is a feeling that there is no where to retreat from and nowhere to retreat to. The landscape has transformed.

Ibrahim says more police were needed back when the clubs were pumping. Maloney also says tougher measures on drunks by police, like old-school overnight arrests and lock up would have been more effective, than breaking up fights and moving people on.

“This whole thing has been cleverly repositioned by the media as an alcohol issue when it is actually a policing issue,” says John Ibrahim.

“We lobbied the state government for two years prior to the introduction of lock out laws, asking for the whole area to be classified as a special event every weekend,” he says.

“When you have 30,000 people arriving at the weekend in The Cross you should have a user pays systems where clubs contribute to the cost of extra policing required. Just like it would be required at a special event or a street party like a festival. We wanted to have an extra thirty policemen on duty every weekend to cope with the influx of people, but this was just brushed under the carpet.”

The clubs are not responsible and not to blame, says Ibrahim. Just look at The Star casino in Pyrmont which as he points out, observes a totally different set of laws to every other venue in The Cross.

“If you want to know what the future of Kings Cross is just walk down Macleay Street and have a look,” says Ibrahim.

“More residential, less high impact entertainment. A trend toward eateries and restaurants,” he says.

“Sydney is just going to be an insane Nanny State. Everyone in the industry has been seeing the writing on the wall, but the public are only just starting to wake up now,” says Justin Maloney.

So what is next for Kings Cross? And what does the death of the district say about Sydney’s attitude to danger, hooliganism and sex? In a place where ‘going up The Cross’ was akin to walking out the door to commit sin, have we really stopped needing this hot bed of sex, drugs and rock n roll, or is there a middle ground? Here’s hoping…