Frida Kahlo and the psychology of the selfie

The selfie. An idea as old as the word is new. The term itself first appeared in an ABC Online forum in 2002, and has caught on like wildfire since; but centuries before that, artists were capturing their own likeness in pigment, not pixels. There’s Rembrandt and Van Gogh and Francis Bacon. But no artist springs to mind quite so much when reflecting on self-portraiture as Frida Kahlo.

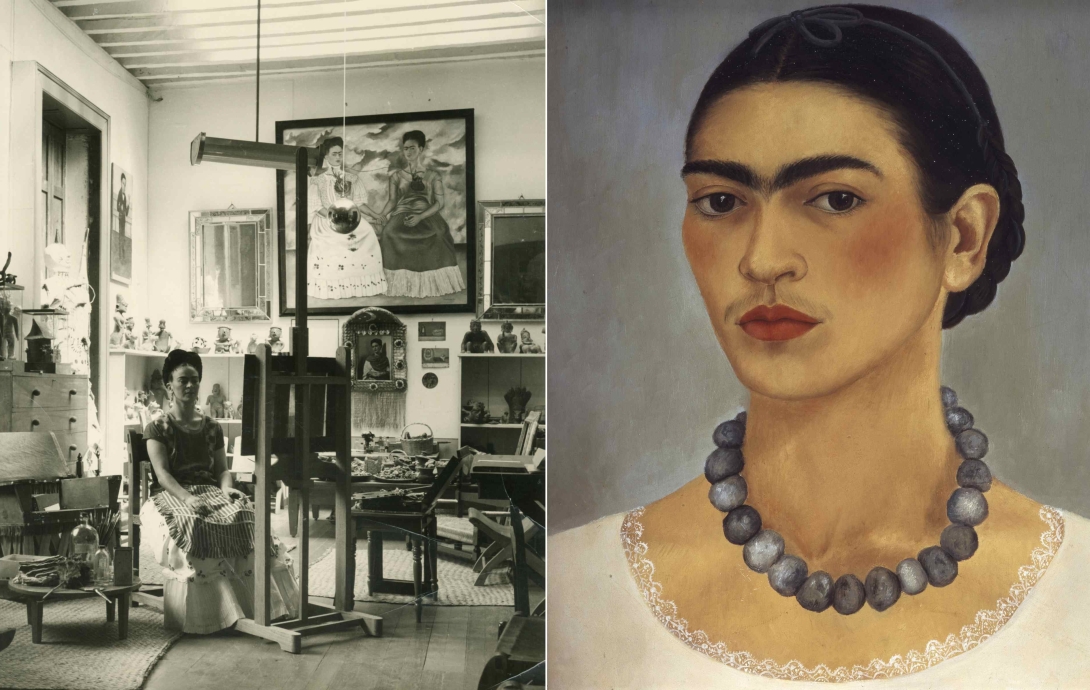

A major exhibition, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera: from the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection, is running now at the Art Gallery of NSW. And while Rivera was a seminal Mexican painter in his own right, all eyes are on Kahlo: on that serious, soulful gaze peering out from beneath those famous dark brows. In those imaginative paintings that speak volumes of the artist and her personal pain (emotional and physical: her tumultuous relationship with Rivera, miscarriage and injuries sustained from a bus crash are all well documented), and of the Mexico – still reeling from the revolution – that she belonged to.

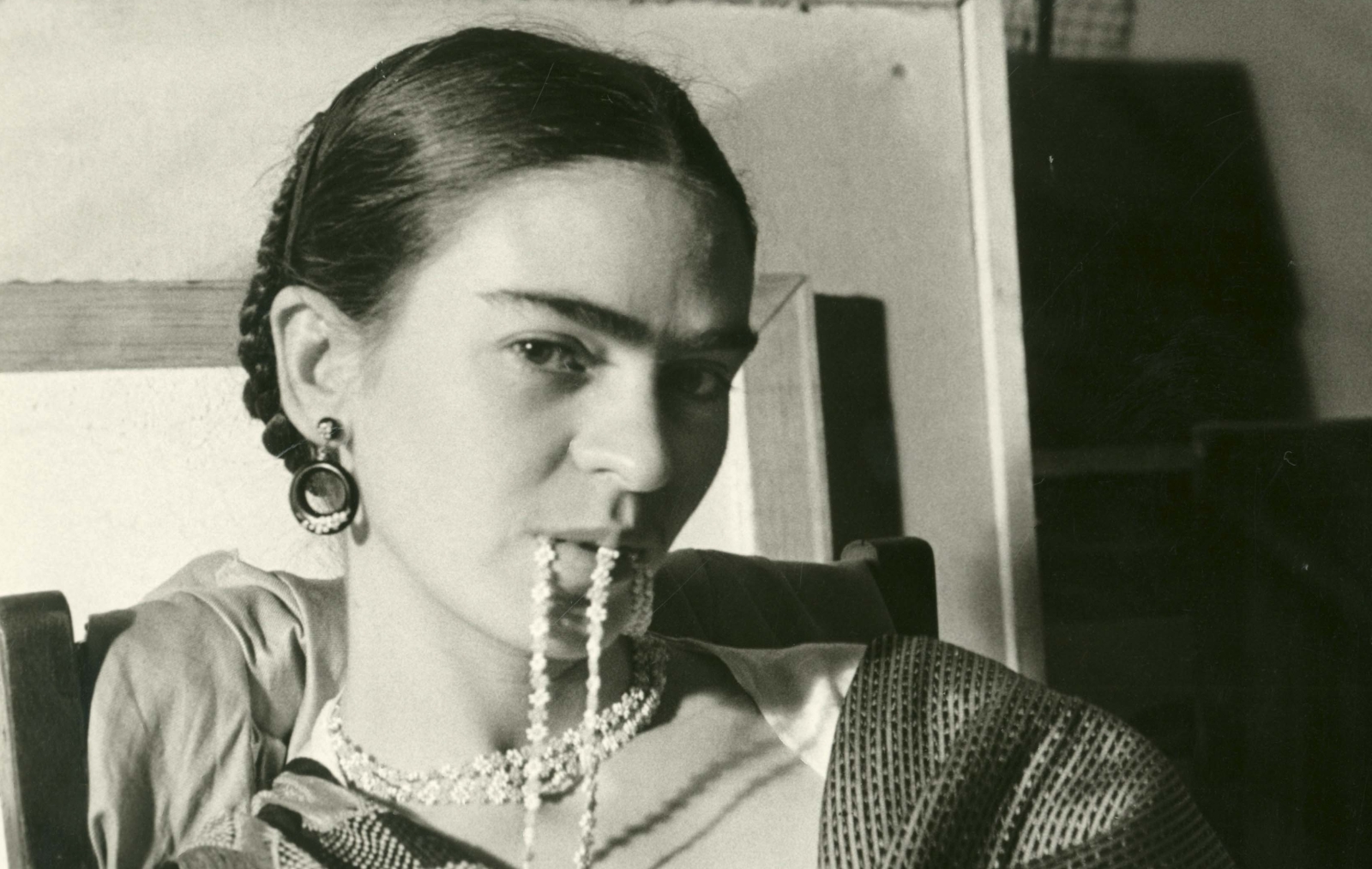

Of the approximately 150 paintings that Kahlo painted before she died at the age of 47, 65 were self-portraits. Of this number, the Art Gallery of NSW is showcasing a concise and intimate selection that includes some of her most recognisable works. But what made the artist document her own image time and time again? At face value, the fact that Kahlo was often bed-bound as a result of her injuries and subsequent surgeries surely contributes; the mirror in easy reach. “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best,” she is often quoted as saying.

But there’s something else at play, which emerges when you contemplate Kahlo’s self-portraits alongside the striking photography included in the show (a combination of portraits and quiet moments shared between the couple, captured by professionals, friends and lovers). “The more time you spend with [the paintings and photographs], you start to realise that [Kahlo’s] self-portraiture project is not a straightforward one, it’s quite a complex thing,” says the exhibition’s curator, Nicholas Chambers. “It’s performative and, as other commentators have suggested, her approach even pre-empts post-modern ways for thinking about the self in art.”

Frida’s father was a commercial photographer and it has been suggested by scholars of her work (most notably Salomon Grimberg) that the first time she saw her own image as a child was in a photograph rather than a mirror. “When she was growing up she was surrounded by photography,” says Chambers. “And I think it’s fair to say that by her twenties she had developed a sophisticated understanding of the medium, and of the way one could work with it to craft a public identity.”

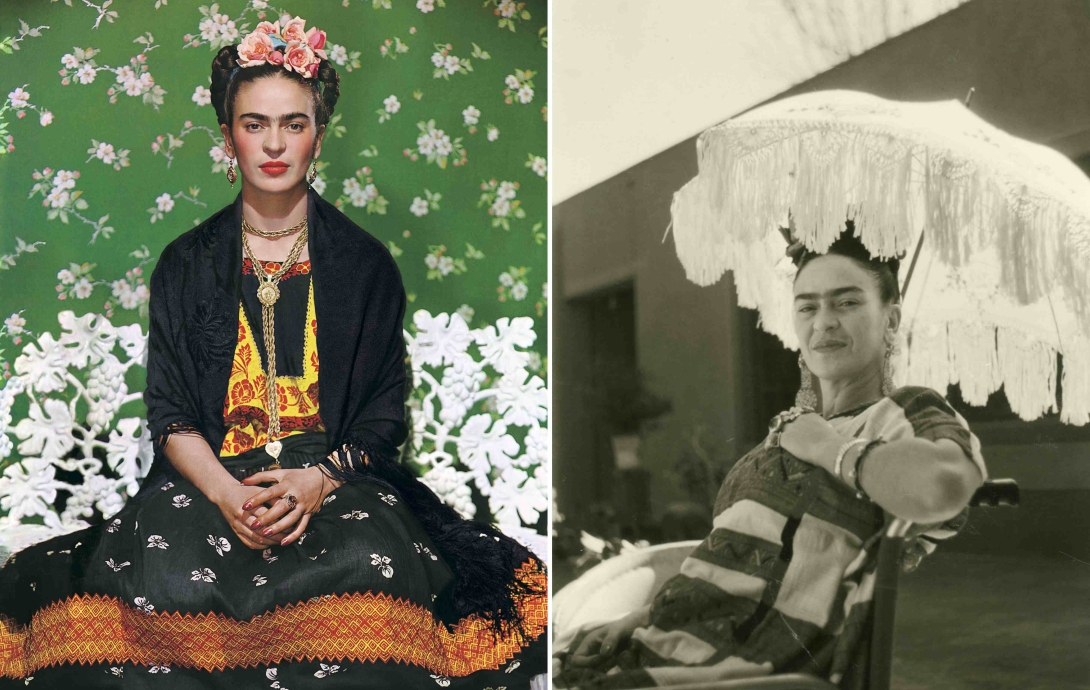

So Kahlo was PR-savvy: and, as Chambers suggests, you can trace her self-invention from these photographs through to her paintings. An example of this self-invention lies in the traditional dress we have come to associate Kahlo’s image with. Rather than an expression of the artist’s actual “Mexican-ness” (she was in fact of mostly Spanish and German descent), Chambers describes this as a “a symbol of her solidarity with the Mexican revolution.” And it is this constructed image that gave rise to her celebrity, cult-like status (‘Fridamania’) both in her lifetime and ever since.

Artist Salote Tawale was invited to present a performance lecture at the Art Gallery of NSW to coincide with the exhibition, and what is striking to her about Kahlo’s self-portraits are the layers of coded meaning painted into the imagery. It’s easy to be dismissive and derisive of the selfie: but maybe they too are ripe with coded meanings, explorations of who we are in this digital revolution. And maybe Kahlo’s motivations for painting self-portraits are not so wildly different to those millions who take to social media with their own careful constructions: what is a selfie if not a means of self-branding?

Chambers doesn’t consider it a huge stretch of the imagination: “Obviously there are completely different factors at play, but conceptually speaking it is very much about the way that one can use images– whether they be painted or photographic – to construct different identities.”

But this point of construction is also the point at which any shared intent dissolves, Tawale considers. Where the selfie is immediate and “you’re knowingly putting yourself into this realm of billions and billions of images”, an artist’s job is to separate from that mass and to consider how a future audience might read and relate to their work. They create “a sort of intimate, but distant relationship with this future audience”, she says.

It’s easy to see the intrinsic value of a Frida Kahlo self-portrait as a cultural document now, while anthropologists are scrabbling to find meaning in today’s slew of self-portraiture. But maybe – who knows? – we might treat selfies with the same respect in the future. “I wonder if archaeologists in 100 years will be combing through a bazillion selfies trying to piece something together!” laughs Tawale. Just as Kahlo painted all the complexity of her person and place into her artwork, so the selfie generation can’t be splashed with broad brushstrokes.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera: from the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection runs at the Art Gallery of NSW until October 9 2016. Due to the show’s popularity, online booking is highly recommended (tickets are dated and timed).