Corporate art collecting

Sitting behind the reception in BresicWhitney’s Darlinghurst office are three screens. Rather than showcasing properties for sale, however, they make up a single artwork.

Conrad Ventur’s 13 Most Beautiful: Screen Tests Revisited is a recreation of screen tests made by Andy Warhol, using the very same men and women, some 45 years later. Filmed in black and white, characterful faces stare out at the viewer, unmoving except for a flit of the eye or twitch of the mouth.

“I sent out emails far and wide, literally the world over, to search for those three channels,” recalls Sydney-based art advisor Mark Hughes. “We bought the second edition and the third was acquired by the Whitney Museum in New York.”

Corporations the world over have long acquired art, with the most famous collections – managed by a staff of curators and bolstered by an army of advisors – belonging to the giants of the financing world. UBS owns over 30,000 works, including the likes of Lucian Freud and Roy Lichtenstein; Deutsche Bank has roughly 60,000.

Nicholas Orchard, head of Corporate Collections for Christie’s Europe, sees two types. The first “an inherited collection that often has a strong historic element; it might include old masters of 19th century art. Then you have the corporate collections that are more dynamic: they’re active and they’re alive. They are art collections which are invested in the here and now.”

For many companies, art is fast becoming more than office decoration. It is a way to bolster a brand whilst, simultaneously, demonstrating corporate responsibility, giving back to the public, and, if done well, a form of investment.

(Upper right) Callum Morton, Pie Eyed, 2000

Deutsche Bank, for example, has “a very active policy of displaying the art, investing in contemporary art, and making sure that the art is relevant for who they are as a company and the messaging they are trying to get out to their clients,” says Orchard. “It helps them raise their profile.”

Critically, insists Ellen-Andrea Seehusen, founder of International Arts Management in Munich, companies want “to show that they are more than products and profits.”

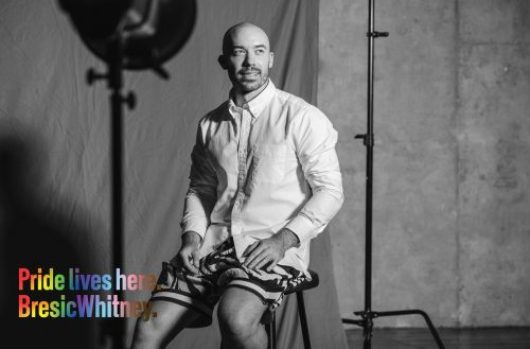

For Shannan Whitney, BresicWhitney’s co-founder, art was one way to establish the personality of the brand. “I wanted our collection to represent the fact that we were contemporary, progressive, edgy, that we are prepared to be bold and risk taking,” he says. “I think art does say a lot to people about who we are.”

A favourite in the collection is Brisbane-based Daniel McKewen’s Running Men, first shown in the 2014 Biennale of Sydney. Five single-channel screens feature movie stars, including Tom Hanks in Forrest Gump and Harrison Ford in Raiders of the Lost Ark, running in a never-ending loop but getting nowhere.

The videos are now scattered throughout the Darlinghurst head office, making unused corners come to life. As Hughes points out Running Man “is all about the anti-hero.” It is an ironic, tongue-in-cheek statement for a company within the real estate industry, an industry in which agents typically presents themselves as “heroes” finalising the deal.

At just under 100 works spread across five offices in Sydney, BresicWhitney’s collection remains tiny compared to the likes of Deutsche Bank and UBS. But, small or big, the hallmarks of a great corporate collection remain the same.

“You have to listen to the client,” maintains Hughes. “The important thing is to try and understand how the art can best represent the client and how the art can have maximum impact for everyone who encounters it.” As for the client, “know your limitations,” he says. “It’s okay to say: I don’t understand, I don’t know, help me. And it takes a lot of confidence to say that.”

Setting practical parameters is also critical, as is preservation and care. “There are things you cannot change: environment, budget, everything from elevator access to structural things, sunlight, high human traffic,” says Hughes, adding: “We’re not going to put a painting that isn’t framed in a high traffic hallway.”

Yet one of the largest pitfalls for corporate collections is not physical, but, in an environment often led by committee who must tick a certain number of boxes, philosophical. Namely, says Hughes, “putting together a boring collection that everyone stops looking at: that is just decoration.”

It is a trap that even the largest of collections have fallen into. In 2005, in a review of the UBS Art Collection at the Museum of Modern Art, The New York Times’ art critic Roberta Smith wrote: “It all seems too pre-approved and risk-free.”

That is changing as the most daring companies are beginning to move away from classic paintings or sculpture to more risky conceptual art says Sam Chatterton Dickson, director of sales at renowned London-based Lisson Gallery.

Last year, as one example, Fidelity commissioned a piece by the Japanese artist Tatsuo Miyajima, known for his use of digital LED counters, for their Tokyo office.

“I think Miyajima’s interest in continuity, connection and eternity, as well as with the flow and span of time and space, has a clear appeal for a financial company dealing literally with the links between numbers and everyday life,” notes Chatteron Dickson.

“In a broader sense conceptual art, as opposed to a figurative painting on the wall, allows the viewer to have greater agency in the ways it can be interpreted,” he says. “This is a very positive message for any company and also gives it kudos for being more adventurous in the kind of art it shows.”

Still, there are challenges. Whitney admits he has made some acquisitions that “cross the line in terms of what people are comfortable with”. In 2002 he purchased a photograph by Australian artist Bill Henson, controversial for his portrayals of partly dressed adolescents. “Some of the staff certainly didn’t feel positive,” says Whitney. “One needs to be considerate.”

(Centre) Hans Op de Beeck, Staging Silence, 2013

Financial returns, too, are not guaranteed. “Who determines what is the right thing to be buying?” asks Orchard. “Often only time can tell.”

For Whitney, however, success rests on the collection’s legacy surviving himself, as founder, to become integral to the future of the company. Hughes agrees “most people making the decisions are highly unlikely to still be in the office in forty years time. So a successful collection evolves over time reflecting the business’ shifts and changes. The art,” he says, “has to take that journey.”