Callan Park: Haunting Histories

My friend studies photography at the Sydney College of Arts at Callan Park, and when she’s in the dark room, she feels strange sensations. Mysterious figures will appear in her photographs.

Like any good haunting, chances are you’ll hear the legend of Callan Park before you go there. Within a month of arriving in Sydney, I heard about the mysterious figures that would appear in photographs from a friend who lives a street away from the park’s boundaries. At night, she too would be overcome by eerie feelings when passing by with her boyfriend. Film crews have rejected filming there. New students are inducted with urban legends of ghost sightings and some refuse to stay back after dark.

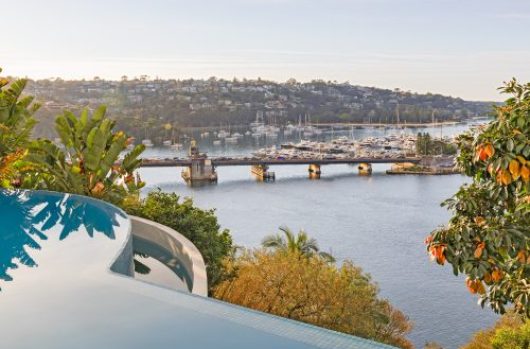

When you walk through the park on a sunlit Spring day, the sun shines, but the shadows harbour a drop in temperature. The vastness of the park’s 150 hectares means that hives of activity occur in the parks corners, each unaware of the others’ existence. Near the park’s edge close to Iron Cove Bay on the Parramatta river, a Sunday afternoon footy game is in full swing. Near the entrance on Balmain Road, writers at the NSW Writers drink coffee and shuffle papers.

But what astounds most when walking through the grounds, is some of its buildings unabashed dilapidation. Next to the footy grounds, a cottage collaged with graffiti has monstera growing out of its smashed windows. Nearby, a pool green with unuse, is fenced off. A silent greenhouse, overgrown, has a statue of an angel gasping for air. The beauty of its degradation hints at its haunting past. Much of the mythos permeating its grounds is due to its 109 year history as the site of a psychiatric hospital. Consisting of a cluster of sandstone buildings known as the Kirkbride Complex, it was initially labelled Callan Park Hospital for the Insane. Although today, the use of the term ‘insane’ is no longer considered apt, in the late 1800’s this was the more politically correct term. Callan Park was originally built to alleviate overcrowding from the nearby Gladesville Hospital of the Insane – a name the medical superintendent Dr Frederic Norton Manning bestowed on it, to help eliminate public prejudice and indifference towards the patients. Its previous moniker was Tarban Creek Lunatic Asylum.

Manning’s resuscitation of these institutions was not just limited to changing their name. Part of the reason he was lured to Sydney for his role as superintendent, was his proposal to tour England, France, Germany and the USA so he could study a range of international techniques in treating patients and the construction of the establishments that housed them. Facilitating what he learned in Europe in Sydney, he transformed Gladesville and Callan Park into places where patients could come to receive treatment rather than merely being held captive in “a cemetery of diseased intellects”.

Manning’s revolutionary treatment was based on moral therapy, which saw ‘insanity’ as a disease of the mind, rather than of the body. Key to patient care was the layout of the building the patients resided in, and together with the architect James Barnet, the two created wards symmetrically arranged along the main cross axis of the official buildings. Each spacious ward, had courtyards overlooking the grounds of Callan Park; the greenery and fresh air seen as a suitable tonic to aid patients in their rehabilitation.

After Manning’s establishment of Callan Park, the facility continued to be a forerunner in mental health care. Along with Gladesville, it was the first in New South Wales in admission without committal, and the first hospital to have a laboratory, where studying pathology of mental diseases in New South Wales began. Despite the hospital’s initial success, overcrowding would soon become a problem, one that occurred as early as 1923, and became exacerbated by the influx of patients during (and in the aftermath of) The Depression and World War II. It was a problem that further construction to the site could not compete with, and would eventually contribute to the stories of trauma that would escape from its halls.

Over this period, hasty additions of basic facilities to Manning and Barnet’s wards not only obscured the original elegance of them, it encroached on patients’ space, and was the exact antithesis of Manning’s moral therapy. The surrounding lawns of the park however, were still places patients could go to coalesce through gardening, as it was thought the patients’ ills could be cured by an “improved environment” and “good honest work.”

And so many of the park’s gardens were kept and cultivated by the patients of the Kirkbride Complex, from the planting of trees, to the laying of its uneven cobblestones.

But there is one war memorial that the park houses that couldn’t be more different in style and contributes to the park’s hotchpotch charm. With rough white walls, terracotta rooves and turquoise arches it is reminiscent of a Mediterranean abode. The two plaques that sit above the once functioning water fountain it guards, have a more Australian feel – the moulded concrete are wreaths of Australian gumnuts, leaves and flowers and pay homage to WWI veterans. But the other monument commemorating WWI, a replica of the Sydney Harbour Bridge straddling a circular wishing well, was erected by patients of Callan Park’s B ward and designed by a WWI veteran himself. Douglas Grant, an Indigenous draughtsman and soldier was captured at the first battle of Bullecourt and became a German prisoner of war for two years. His ethnicity made him of interest to German anthropologists, and yet he survived the trauma to come back to Sydney and pay homage to his fellow countrymen who had died serving.

Despite this, there are no monuments in the park that commemorate the original inhabitants of Callan Park; the Wangal who were part of the Eora or Dharug tribes. They lived on the site now known as Callan Point, a site which extends along the Parramatta River to Petersham. They too, experienced mass trauma, as during a period of one year; between 1789 to 1790, a small pox epidemic wiped the majority of their population out, as did subsequent European land development, which meant that by 1900, there were only 50 people from Dharug families still living. These are the original hauntings of Callan Park that the others have been layered upon – stories left untold heralding more to come.

After decades of overcrowding, of stench, straightjackets and investigations resulting in little to no improvement, in 1976, Callan Park closed its doors and amalgamated with the Broughton hall Psychiatric Clinic to become Rozelle Hospital. But after a renovation in 1996 the Kirkbride Complex sandstone structure transmuted into Sydney University’s Sydney College of the Arts, giving budding artists a unique setting to capture their inner muse and form a tight-knit creative community within their own campus.

But now the art students will vanish too. Plans are to relocate the Sydney College of the Arts to a smaller space at the Old Teachers’ College in Camperdown due to dwindling student numbers and funding cuts. The move is expected to occur in 2019. So, it too will close its doors, despite major protests from its pupils and teachers. And the park’s viability is also quivering – either the Minister and the Office of Environment and Heritage must get adequate funding to finalise the Callan Park Master Plan, which aims to protect and preserve the park, or it may be sold to developers.

Although some of the buildings at Callan Park are still in use, the degradation of others seems like an utter waste. The grounds are reminiscent of the abode of the Dickensian Miss Havisham, the potential of ‘what could be’ still evident. Fertile grounds for writers, artists, footy players and all the ghosts to wander.