Inside Sydney’s abandoned power station

You’ve seen the White Bay Power Station as you’ve crossed the Anzac Bridge from the city. And by now you’ve probably heard the news: Google might be moving into this strikingly dilapidated building. Last week the NSW State government revealed plans to transform this heritage-listed, 10-hectare waterfront site into a tech hub to rival London’s Tech City and California’s Silicon Valley. Set to become the beating heart of The Bays Precinct (Sydney’s biggest urban development project since the 2000 Olympics), the tech giant wants to turn the space into the Google Australia Innovation Hub at White Bay. Other concepts gleaned from the government’s public Call for Great Ideas include Grimshaw’s renewable energy station and Woods Bagot’s mixed-used hub for science and technology.

Whichever route the government shoots for in the near future, what’s clear is its vision of revamping the original building to create a new neighbourhood precinct: think cool new places to live and work, galleries, a village-like hub of shops and restaurants and a waterfront forecourt.

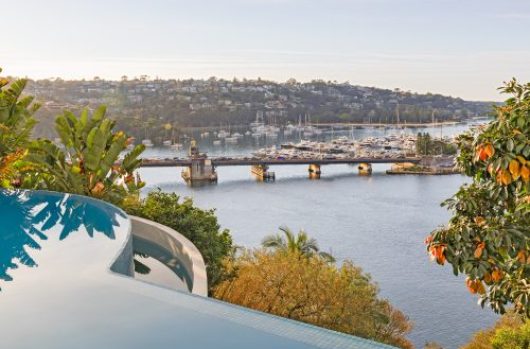

But before we leap into the future, let’s consider its history and what makes this site so desirable. For a start, the White Bay Power Station is a relic of Sydney’s lost industrial age that once kept our trains and trams moving by coal-fire. It reminds us of when its neighbouring suburbs Balmain and Rozelle were not the affluent residential hubs we know today but blue-collar, industrial enclaves. In fact, the power station marked the entrance to the Balmain industrial waterfront.

With a dramatic vertical façade and soaring chimneys, it’s been a landmark ever since it opened in 1917. But where once this type of harbourfront complex was a common sight in Sydney, it’s now the last remaining example and has taken on a more mysterious vibe. Today it cuts a stark figure on the horizon, popping suddenly into view like a castle from a dark fairytale: it’s not surprising that is was used as a location for Baz Luhrmann’s film The Great Gatsby in 2011.

From the outside the power station also strikes us in its decay: its Federation-era foundation bears layers of city dirt and is flanked by corrugated iron retrofits that have rusted to all shades of brown and orange. And those few who have been able to peer inside the space since it shut down in 1984 are inspired by its cathedral-like properties.

Matthias Irger is one person who’s had the chance. An architect, urbanist, analyst and lecturer on UNSW’s Built Environment degree course, his students were among those encouraged to submit proposals for the Call for Great Ideas.

“The most striking aspect of the power station from an interior architectural point of view is the sheer scale of the space that we have inside,” he describes. “The height of the ceiling, the length of the building… I think it’s one of the longest buildings in NSW if not in Australia.”

And while its future is still hanging in the balance, it’s hard not to think about famous industrial-site-to-art-centre-conversions when contemplating this. Carriageworks in Eveleigh, the Powerhouse Museum in Ultimo or the Tate Modern in London are prime examples. “An art gallery could be an appropriate use for it because it’s utilising this immense scale of the building and the quality of the space,” Irger says, but for him a combination of residential development, job-creation and culture would be key: “you really need a holistic approach to combine as many usages as possible to make it as resilient, future-proof as possible.”

Throughout all of this, maintaining the site’s history and integrity will be the way forward. Much like we’ve seen with Carriageworks, this is an exciting and bold step for Sydney: converting old energy to new and reimagining our past to enrich our future.